Rotating matrices

Does an invertible matrix stay invertible if you rotate its rows?

This project is designed to give an introduction to this write-up, which is based on the final chapter of my masters dissertation.

Unlocking matrices by row rotations

A slightly random but fun question we can ask is: given a matrix, when can we rotate its rows to make it invertible? We will say that a matrix can be unlocked if there is a way we can rotate its rows so that it becomes invertible.

Examples

For example, the matrix \(\pi = \begin{pmatrix} 3 & -1 & -4 \\ 1 & 5 & -9 \\ 2 & -6 & 5 \end{pmatrix}\) is not currently invertible since \(\det(\pi)\)=0. However, \(\begin{pmatrix} 3 & -1 & -4 \\ 1 & 5 & -9 \\ -6 & 5 & 2 \end{pmatrix}\), the matrix we get if we rotate the 3rd row to the left by one column, has determinant -27 and thus is invertible. So \(\pi\) can indeed be unlocked.

Now let’s look at another example. Take \(\gamma = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & -7 & 5 \\ -3 & -8 & 11 \\ 2 & 0 & -2 \end{pmatrix}\). However hard you try, you will never be able to rotate the rows of \(\gamma\) such that its determinant is non-zero and thus \(\gamma\) can never be unlocked. A clever way to see why this happens is to notice that the digits in each row of \(\gamma\) add up to 0. Thus, \((1,1,1)\) is an eigenvector of \(\gamma\) with eigenvalue 0 no matter how we rotate the rows. Since the determinant of a matrix is equal to the product of its eigenvalues then the determinant of \(\gamma\) is always zero.

Using the same logic, we can see that any matrix where all its rows add up to 0 can never be unlocked. We might conjecture that if the rows of a matrix do not all add up to 0, then it can be unlocked. However, an easy counterexample is the matrix containing all 1s. A more interesting example of a matrix that can never be unlocked is \(\rho = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ a & b & c & d \end{pmatrix}\) where \(a\),\(b\),\(c\) and \(d\) can be any numbers. We can notice that the first 3 rows of \(\rho\) will never be linearly independent no matter how we rotate them and thus the determinant will always be zero.

Having seen these different examples, it might not even seem like there would be an exact condition on when a matrix can be unlocked? Surprisingly, there is - we just need the help of a little bit of algebraic geometry and graph theory. The original idea for the following construction comes from (Kézdy & Snevily, 2004) which has been built-upon in (Brauch et al., 2014), however, both focus on a small class of matrices and only over the complex numbers. In this write-up, we extend these ideas to work for any matrix over any field.

A little bit of algebraic geometry

Assume we are a given an \(n \times n\) matrix \(M\). We will assume we are working over the complex numbers for now as we will need \(n\) distinct roots of unity. We start by defining polynomials \(g_i(x_i) := \sum_{j=1}^{n} M_{ij} x_i^{j-1}\) for \(i \in \{1,...,n\}\). All we need to know about the \(g_i\)’s is that they each encode the information of the \(i\)th row of our matrix \(M\) in polynomial form. We now define another polynomial \(f_M(x_1,...,x_n) := \prod_{1 \le j < k \le n} (x_k-x_j) \sum_{i=1}^{n} g_i(x_i)\). While \(f_M\) may look fairly arbitrary, its key features are that it contains all the information about our matrix \(M\) (both the elements of \(M\) and their positions) and it vanishes on any input \((x_1,...,x_n)\) where \(x_i = x_j\) for some \(i \neq j\).

The magic part is that if we expand \(f_M\) into a sum of monomials modulo the ideal \(\mathcal{I} := \langle x_1^n-1,...,x_n^n-1 \rangle\), the coefficient of each monomial is the determinant of the matrix given by rotating the rows of \(M\) according to said monomial up to a sign change. Thus \(M\) cannot be unlocked if and only if \(f_M \in \mathcal{I}\).

While this is an exact condition on \(M\) being able to be unlocked, which is what we were looking for, \(f_M\) is not a very intuitive polynomial and we haven’t used any graph theory yet!

A little bit of graph theory

We will need two key pieces of graph theory to get a nic exact condition on when our matrix \(M\) can be unlocked.

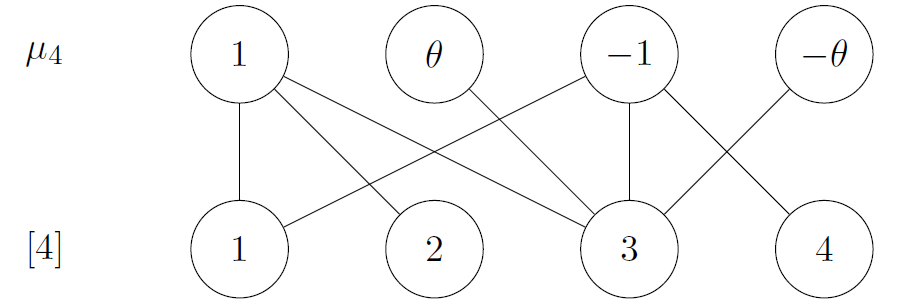

The first key piece of graph theory we will need is bipartite graphs which are graphs whose vertices are partitioned into two sets where no two vertices lying in the same set share an edge. So let’s define a bipartite graph \(G_M\) with the first edge set being \(\{1,...,n\}\) and the second being the set of \(n\)th roots of unity which we will denote \(\mu_n\). Now, let \(i \in \{1,...,n\}\) and let \(z\) be an \(n\)th root of unity. Given our matrix \(M\) and our polynomials \(g_i\), there is an edge connecting \(i\) and \(z\) if and only if \(g_i(z) \neq 0\). Figure 1 at the top of the page shows the bipartite graph \(G_M\) where \(\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 0 & 2 & 5 \\ -1 & 1 & -1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\theta^2 = -1\).

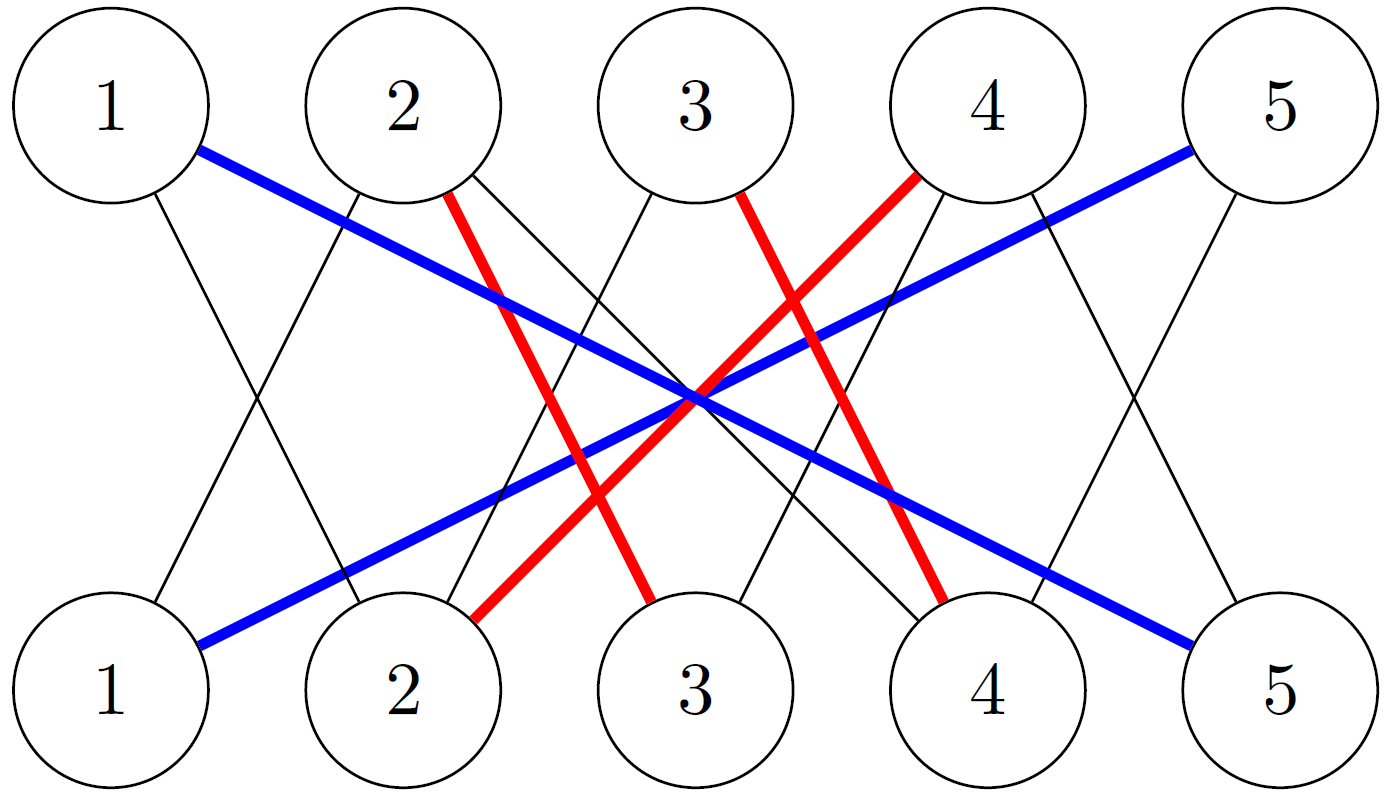

The second key piece of graph theory we will need is perfect matchings on a bipartite graph. As you might have guessed from the name, a perfect matching on a bipartite graph with \(2n\) vertices is \(n\) edges which touch all vertices in the graph. A perfect matching is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Now we can finally state the exact condition.

Theorem: A matrix \(M\) can be unlocked if and only if \(G_M\) contains a perfect matching.

The final step of the proof uses an extraordinary and incredibly useful result called the Combinatorial Nullstellensatz, which first appeared in Alon’s paper (Alon, 1999) and crops up all the time in algebraic geometry, combinatorics and graph theory however it is slightly too wordy to include in this overview.

Conclusion

While this connection between when matrices can be unlocked and when bipartite graphs have perfect matchings seems a bit magical at first, it seems less random when it is put in context by Kézdy and Snevily’s paper (Kézdy & Snevily, 2004).

However there are more many questions we could go on to ask. What happens if we allow both row and column rotations? What happens if we are allowed to permute the elements of our matrix at will?

All is revealed in this write-up and we in fact answer the latter question before the former using lots of graph theory along the way.

References

2014

- The Combinatorial Nullstellensatz and DFT on Perfect Matchings in Bipartite GraphsArs Combinatoria, 2014

2004

- Polynomials that Vanish on Distinct nth Roots of Unity.Combinatorics, Probability and Computing, 2004